If implemented, the proposed reform of the Copyright Act that was out for consultation will weaken the rights of those working in the fields of culture, information and entertainment. This involves, among other things, undermining the copyright protection of authors, publishers and filmmakers, destroying the huge economic potential of the authors of television programmes, making it more difficult to agree on the use of works and even complicating the work of teachers.

The amendment proposed in the draft is so radical that it should have been prepared in advance by a separate working group, rather than being first introduced in the draft proposal.

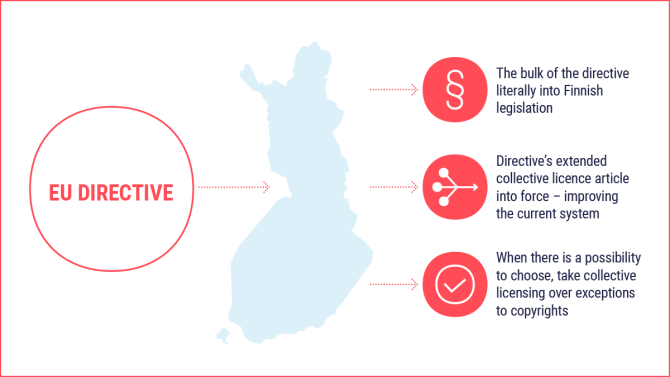

The amendments to the Act are based on the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market (DSM Directive), which harmonises the Digital Single Market, and the Online Broadcasting Directive. The consultation on the draft proposal prepared by government officials closed in early November and attracted a record number of 223 statements. Due to the exceptionally large number of statements, the Ministry of Education and Culture, which is responsible for the preparation, is facing a huge reading task and important policy decisions at the end of 2021.

The time needed to read, analyse and draw conclusions from the statements, as well as for political consideration, means that the government’s proposal is likely to be delayed until 2022.

This time-out is much needed. Many of the statements on the draft law expressed astonishment, criticism and even outright rejection in many areas. The vast majority of statements criticised the lack of proper preparation and impact assessment of the amendments. The statements highlight the fact that many details of the draft need to be changed and improved before the proposal can even proceed to the next stage, the finalisation of the government proposal.

Feedback highlights many shortcomings of the proposal

The draft proposal contains national copyright policies that go well beyond the requirements of the directives. Many of the proposed national amendments came as a complete surprise to stakeholders. Typically, a working group or groups are set up to prepare legislative changes, reconciling the different views of those affected by the law. In this project, this was not the case.

One example is the policy on teaching materials. The DSM Directive requires a limitation of copyright regarding illustration for teaching to be included in legislation, but the approach taken in the draft proposal differs significantly from the Directive. According to the draft proposal, materials used for teaching would be subject to a full copyright limitation – a compulsory licence – with remunerations paid by the state. The amendment proposed in the draft is so radical that it should have been prepared in advance by a separate working group, rather than being first introduced in the draft proposal.

Copyright holders, users of copyrighted materials and citizens deserve an amendment that will result in a balanced, modern and functional Copyright Act in Finland.

Sufficient time must now be allowed for a new preparation, leading to corrections in line with the feedback. Although Finland is already the subject of an infringement procedure initiated by the European Commission, there is a clear justification for the time-out. The majority of statements called for reconsideration or further preparation. This was also the position of Kopiosto.

The dialogue between decision-makers and drafters in the Ministry of Education and Culture now plays a crucial role in considering the feedback and deciding on further preparation, and later on the formulation of copyright policy.

Copyright holders, users of copyrighted materials and citizens deserve an amendment that will result in a balanced, modern and functional Copyright Act in Finland. I believe that political decision-makers also have the will to achieve this goal.

– Valtteri Niiranen, CEO of Kopiosto

Photo: Suvituuli Kankaanpää